We are so excited to have Christy Chase join us today to share information about Community Picture Books!

Christy earned her MFA from the Writing for Children and Young Adults program at Vermont College of Fine Arts in July, 2023. Before that, she taught grades 4-8 in a variety of elementary and middle schools. She has a lifelong love of children’s literature, particularly picture books. She is currently writing picture books, chapter books, a middle grade novel-in-verse, and poetry. She lives in Pawtucket, RI, where she stares out the window thinking really hard, and where she teaches Iyengar yoga.

There are many types of picture books for kids on the theme of community. And rightly so; feeling connected to the people and places around you is an essential part of being a healthy human.

Sometimes this theme is interpreted as looking at the different roles people have, such as police officer, firefighter, baker, nurse, etc. In kidlit, these might be nonfiction, and can be part of a series.

We can also look at geographic communities, such as a suburban neighborhood, city block, or rural town, to see what makes them tick. Or, some books compare geographic traits with similar communities around the world.

Another interpretation of a community-themed book is to tell a story about groups of people; for example, within extended families, faith congregations, or school settings. Some look at groups that share similar physical traits, identities, or culturally-connected customs.

Finally, some picture books highlight individual characters who help their community, discover their ability to create positive change, and bring people together.

I’m sharing a handful out of the giant pile of books you can find about communities. Hopefully, you’ll find at least one that makes you laugh, tugs at your heart-strings, or inspires you.

In the Neighborhood by Rocio Bonilla

I fell in love with this humorous, animal-filled tale about neighbors who are strangers. Each makes an incorrect assumption about the neighbor next door, until one day, the owl’s internet goes out and Matilda, the very handy robot designer, is able to help her. A domino effect occurs, and in the end, you can guess, a happy community is created. The roles held by – and the personalities of – the animals are ones often seen within a child reader’s own community. Very clever, detailed, beautiful watercolor illustrations.

Hey, Wall: A Story of Art and Community by Susan Verde, illustrated by John Parra

Told through the voice of a boy, this book features diverse characters in an urban setting. Colorful community members share food, dancing, memories, laughter, but the wall is just a plain concrete nothing. The boy has a dream of how to change it, and gathers folks to design the transformation. “Hey, Wall! Look at you now. You are beautiful. Now you tell the real story of us. And together we are somethin’ to see!”

Hey, Wall honors a child’s dream to create beauty out of drab concrete with the help of his community. Vibrantly illustrated by John Parra.

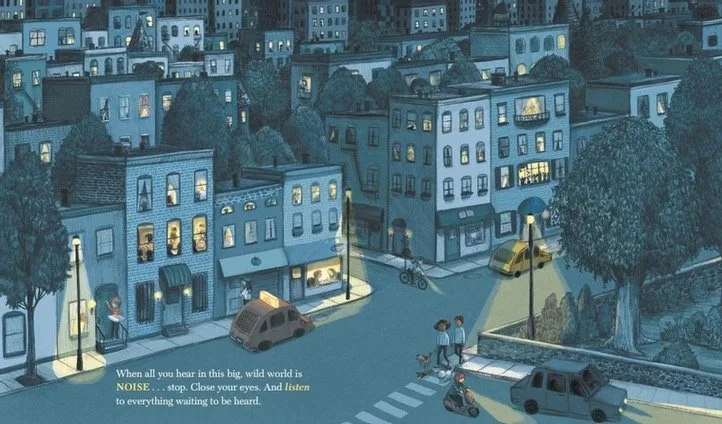

Everybody in the Red Brick Building by Anne Wynter, illustrated by Oge Mora

This book is a visual and aural feast. Wynter uses onomatopoeia and repetition in a circular format to show how a diverse community of families who share an apartment building are awakened in the night, and then go back to sleep. This is a great read aloud if you’re into making fun sounds, and there is the opportunity for a wide variety of kids to see themselves in the cutout illustrations done by the fabulous Oge Mora.

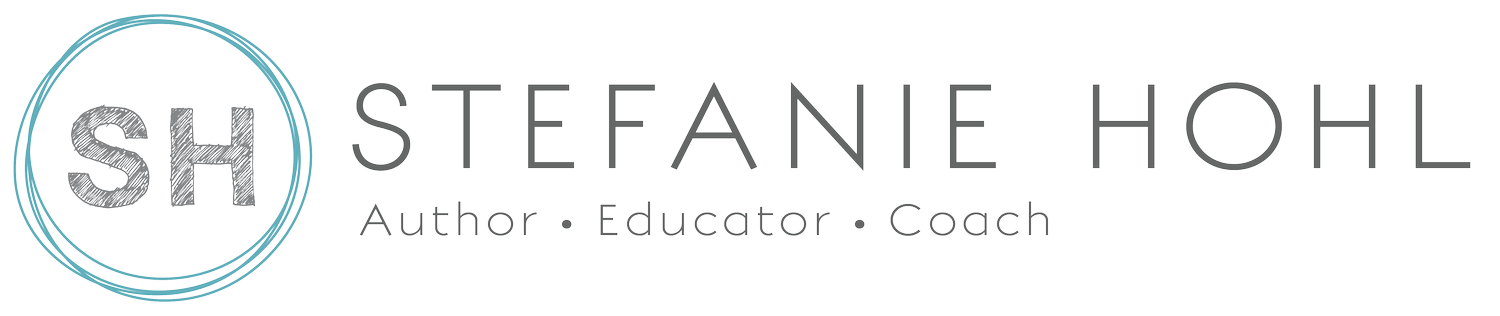

Dear Street by Lindsay Zier-Vogel, illustrated Caroline Bonne-Müller

I think you will be inspired to go out and write love letters to your community after reading this heartwarming picture book. As the text cycles through the seasons, Alice hears neighbors grumbling about the usual things: the weather, chores, construction, etc. She spreads positivity by leaving love letters around the neighborhood for those who might need an attitude adjustment.

In real life, the author created the Love Lettering Project, which then inspired her to write this book for children.

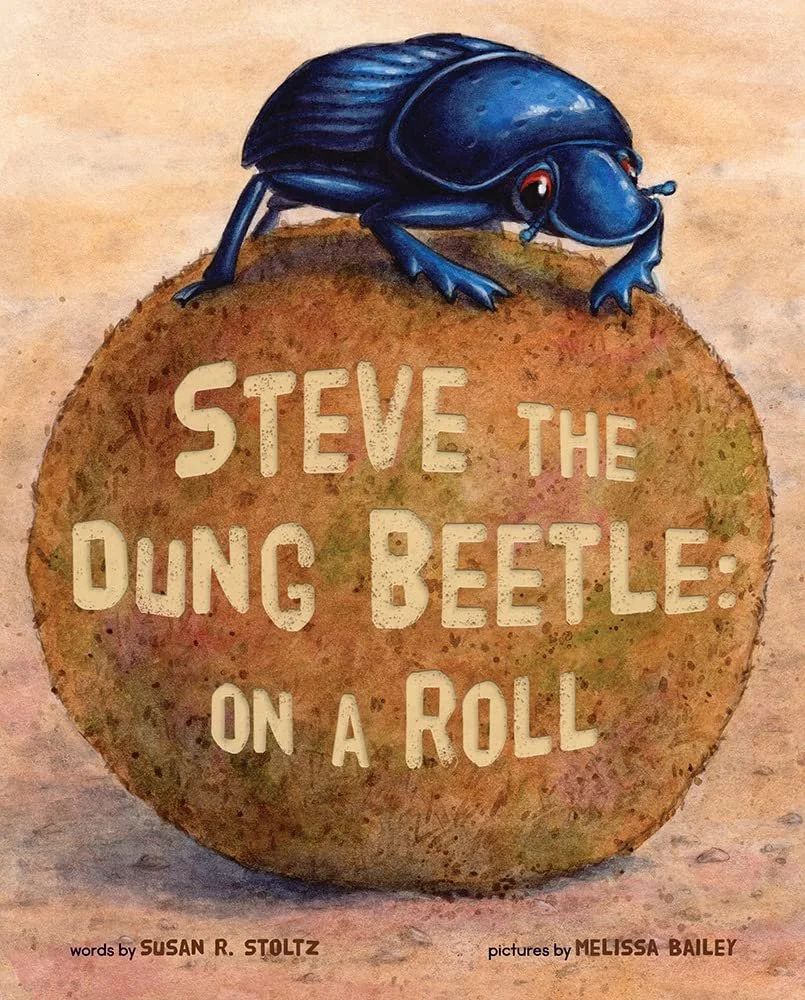

Steve the Dung Beetle: On a Roll by Susan R. Stolz, illustrated by Melissa Bailey

Don’t be thrown off by the very funny title: this book is about how an individual can positively impact the flora and fauna of their community. In this case, the helpful individual is a dung beetle who bumps into other animals of the savannah as he rolls poo around. Readers will learn how not gross this is. Plenty of backmatter about all the animals and beautiful illustrations make this an interesting, laugh-out-loud choice for kids!

The Walk by Winsome Bingham, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

A Black girl and her grandmother take a long walk through their neighborhood, gathering friends along the way. The reader isn’t told their destination, but a few hints are given in the dialogue and illustrations as their group builds in number. The walk brings together a community which finally arrives at the girl’s school to vote. When the girl asks, “Why do people vote?” the grandmother responds, “For HOPE, baby.”

Bingham’s lyrical text uses rhythm and slant rhyme masterfully, making this a great read-aloud with lots of heart. It can prompt meaningful conversations with kids about subjects like history, intergenerational relationships, and how important voting is for a community.

One of my favorite illustrators is E.B. Lewis, who captures setting and characters’ emotions so well. He depicts characters of a variety of abilities, colors, ages, and shapes. Personally, I’m a little burnt out on the overly-digital artwork that prevails these days, so his watercolor paintings here are a feast for my eyes. This story deserves his artwork.